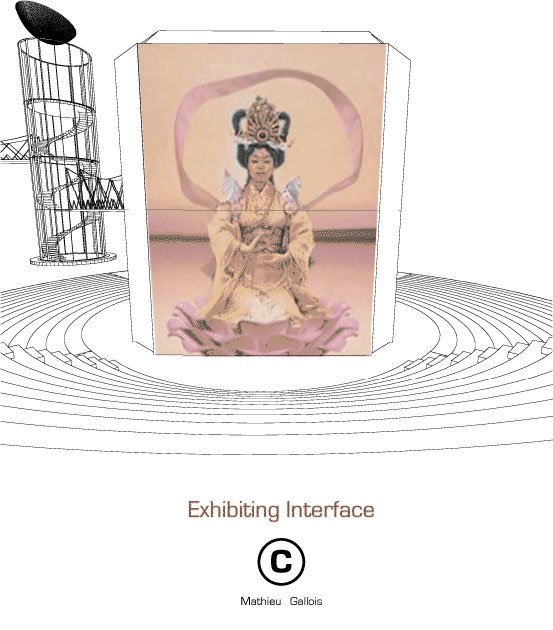

Exhibiting Interface

Multimedia Project Space

Museum of Contemporary Art

Sydney Australia

Introduction

The following proposal is an initial, abbreviated outline and rationale of a multimedia project space for the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney.

Please note that, at this developmental stage, the project vision is fluid – this proposal has been compiled to generate feed back, and to further interest and funding in the project.

01 — Description of concept: an Exhibiting Interface

The (concept) space is conceived as a highly flexible tool: the function(ality) of which is to serve the artist and his / her art project(s) – affording maximum control and flexibility over the designated exhibiting environment.

The structure consists of a subterranean infrastructure that ‘feeds’ a ground level exhibiting platform or volume that is at once multifunctional and without a predetermined architectural form. As an ever evolving and ever changing space, the concept suggests a reading or architecture that, over time, is animated and performative.

The overall size of the concept is flexible (the accompanying drawings detail a proposed site that is 32 metres in diameter). The project space is located between the existing MCA and the main Circular Quay pedestrian thoroughfare and has its own underground vehicle access.

Four flexible viewing areas surround a central exhibition space / platform(s). The entire structure is suspended on a hydraulic system; its parts are movable, removable, and interchangeable. An important feature of the design are a number of large wall-sized, structural, digital screens, each measuring 11 x 5 metres. The screens can either form a vast three-dimensional architectural broadcasting platform, which has a potential surface area over two floors totalling 440 sqm, or be individually manipulated in a number of configurations across the site. The screens can be used both to display video art and film in innovative ways, and to act as billboards to advertise present and future exhibitions / cultural events in Sydney. Potentially, the space can be configured to allow direct access to the exhibited art from the Circular Quay pedestrian thoroughfare. Alternatively, the four enclosed theatres can be raised, allowing 1600 patrons to view four different films or videos, or to collectively view a single live performance within the confines and comforts of a traditional seated theatre. Many combinations between these two polar settings can be configured; for example, the cinemas can be used at a subterranean level – freeing the ground level site.

To further facilitate the manipulation of the site, to form a direct link to the existing MCA Maritime Building and to provide access for potential 2nd and 3rd levels of gallery space, a service tower flanks the site. (The tower is separate from the main site to further liberate the building’s movement and manipulation.) The tower houses a stairwell, lift and bridge. The tower, or the existing MCA (as a way of reinforcing the link between the two sites), could house a large satellite dish, acting not only as a tool, but also as a visual sign of the concept’s connectedness to the rest of the world.

It is important to point out that the Project Space represents a relatively minimal intervention on the Circular Quay site. Significantly the whole structure can be, literally, closed down, leaving just a flat platform, 15 metres in diameter, that can be walked across and used in much the same way it is used today as an undeveloped public site. The core exhibiting space, when raised, addresses a wide area; however, its structure is small, with a base that covers 124 sqm. The open public area around the existing MCA measures 17,200 sqm. Even when fully activated, the Project Space covers an area that is only 32 metres in circumference or 340 sqm in surface area.

Significantly for a project space, the concept allows for exhibitions to be simultaneously exhibited at ground level, and to be planned and assembled in preparation for installation in the subterranean infrastructure, allowing for the quick turnaround of exhibitions.

Applications — a public project space / volume that can be:

Multimedia visual arts exhibiting space

Multimedia broadcasting and receiving centre

Flexible pedestrian scape public gallery

Public, night-time open air film and video centre

Cinema / theatre /auditorium / lecture theatre / conference centre

Commercial exhibition space

Sports stadium

Or a combination of the above.

02 — Precedents

Contemporary arts spaces, in the western world, tend to follow three broad architectural models / strategies.

The most common contemporary arts space (found in most urban centres) is a purpose built and designed building that follows (in general terms) a pared down modernist rationale that seeks to create neutral white cube spaces. The building’s purpose and functionality primarily serves the displaying and viewing of the art.

In the second and most sensational model, the sculptural design of the building, its architectural expression, is the dominating factor in its conception. This model seeks to encapsulate and express the values of contemporary visual culture; the building acts as a cultural icon. A recent example is Frank Gehry’s Bilbao Museum in Spain. In this model the architect’s vision permeates and sometimes eclipses the art on display.

The third model renovates an existing building, transforming the space into a contemporary arts space. In this model, the emphasis is on creating both neutral spaces within the existing architecture, and allowing room for the displays and artists to interact with the history of the building. The New Tate Museum in London is an excellent example of this model; the main ‘turbine room’ acts as a major project space for site-specific works.

The most significant architectural influence on the Project Space conception is Richard Rogers and Renvo Piano’s Pompidou Centre in Paris, France (1971 –77). Designed with the building’s service infrastructure placed on the outside of the building to free the internal spaces, the building was also initially designed to allow for the manipulation of whole floors. On the monumental scale of the Pompidou Centre (over 400 000 sqm of floor space – and with trusses spanning entire 100 metre floors) the latter proved to be too difficult to actualise.

03 — Guiding Principles

Create an exhibition space that meets the multimedia demands of 21st century art.

Create a high technology project space designed to act as an exhibiting tool for artists.

Create an uniquely dynamic project space as incentive / draw card to attract the world’s best artists to Australia.

In form and placement, seek to bridge the threshold between public/pedestrian Circular Quay and existing MCA.

Complement, rather than replace the existing (popular) historic Maritime building. The white cube is a great model for displaying art – the MCA has four levels of white cube exhibiting space that adequately serves many of the MCA’s exhibiting requirements.

Create an economical space with commercial income generating potential. Small means flexible, small means economical. Relative to the proposed redevelopments of the MCA submitted in 2001, the project space is a highly economical proposal costing millions rather than tens or hundreds of millions of dollars (Federation Square in Melbourne cost in excess of 400 million dollars). The project space’s ongoing running cost would be offset by the concept’s income generating facilities.

04 — Rationale

The concept and design of galleries has not changed substantially in hundreds of years, whereas, almost by definition, today’s artists are employing almost any medium within any context to create art. Creating site-specific works (some of which are monumental), soundscapes, virtual realities, using multimedia technologies, making films, television documentaries, going ‘live’, recreating historical events as performance (the list goes on and on), as well as employing traditional means and materials, is standard practice.

Within these broadened parameters, the problem of exhibiting art to a mass public has not been addressed. Many of the great site-specific works of our era have only been experienced first hand by a select few enthusiasts.

Contemporary art has outgrown its existing infrastructure. It has to some extent exhausted its conceptual and physical possibilities, and is now being restrained by existing architectural frameworks best suited to hanging painting and displaying object-based sculptures.

What will art look like in twenty years’ time? The project space, with no predetermined form, and a highly flexible subterranean support infrastructure, is conceived to address some of contemporary art’s present needs, and also to be a project space that can accommodate future media and technologies (please see futuristic proposal that accompanies this proposal).

It is important to consider this concept proposal for Sydney’s MCA within an international context. Contemporary visual art is an increasingly globalised phenomenon – major exhibitions tour the world, successful artists exhibit simultaneously across the globe, and, through new telecommunications media, the whole world keeps abreast of major developments and exciting new art works.

With its small population, tiny art market, and remote global position, Australia’s international visual art profile is, in real terms, very low. Only very occasionally does art made in Australia figure in any shape or form in the international art press. In a very competitive international art scene, most artists are highly conscious of their need to constantly maximise their profiles. The art world is enormously hierarchical – artists have a heightened awareness of the status of each country, city, and art space in which they exhibit. From the perspective of a ‘hot’ international artist, the prospect of exhibiting in Australia holds few incentives.

Redeveloping or creating another MCA along existing models and strategies does not address Australia’s geographic and cultural isolation. Such a building risks being just another generic MCA on the international arts circuit, not a significant departure from its present status. Australia needs to take the incentive, address its status and isolation in the art world, and create a truly novel exhibiting experience that will both draw international artists to Australia and provide an international platform, in Australia, for Australian artists.

05 — Background

Why and how did I come to conceive a project space for the MCA?

A happy accident – I did not set out to conceive an alternative type of contemporary arts exhibiting space, but found myself during a dry lecture on democracy and art at Goldsmiths College in 2003 (where I completed an MA in Visual Arts), pouring ideas onto my notebook. With the benefit of hindsight, I can see how my experiences and preferences as a practicing artist, my work experiences at Fox Studios and Opera Australia, and my lifelong interest in architecture, came together in a happy accident.

At some point during the highly publicised selection process for an architectural team to re-develop the MCA, I reflected on the curious fact that artists themselves generally seem to be excluded from the conception and (re)development of contemporary arts spaces.

Artists view contemporary art spaces differently from architects.

As a practicing visual artist with a strong predilection for creating major site-specific art projects (I have exhibited over 35 times, however, I feel that I have only made successful site-specific works outside of traditional gallery spaces), the‘ white box’ art gallery space has been first and foremost a problem that I spent the last 10 years trying to resolve.

Recently I have engaged in studies in architecture at University of Technology Sydney. At this point however, the great influences on my architectural thinking have come through my practical, hands-on, work experiences here in Sydney, in film and theatre production.

At Fox Studios, working on the cult sci-fi film The Matrix in 1998, I was introduced to the film set; the model of a purpose-built space that acts as a blank sheet for the production of culture. I was fascinated by these vast purpose-built spaces that were loaded with technology and infrastructure – spaces that acted as enormous tools and factories for the imagination. I could not but help compare the generally impoverished production of fine art and the production of film. Working on The Matrix (which had a budget of $100 million), I came to understand that, in our day and age, it is possible to make almost anything – it was a liberating realisation.

At Opera Australia, where I worked as a set builder, a lot of our time was spent creating specially designed sets that could be fitted into the impossibly small backstage wings of the Sydney Opera House. Everything we made had to be economical in size and purpose, so that it could be easily and quickly assembled and dismantled within the confines of the wings and the limited time frame between acts. By default, I was introduced to a whole method of construction, an idea of architecture that was completely manipulable and mobile.